Six years ago, Colorado made history by ending marijuana prohibition, unleashing a new industry and a million pot jokes.

Much of what the state and municipalities predicted to come from the legal recreational use of cannabis has happened. It’s relatively inexpensive, convenient and unobtrusive in our society.

Cannabis sales average around $1.6 billion a year, according to state officials. Since legalizations, consumers have forked over upwards of $8 billion dollars.

But there have been surprises, too. Read on and see what the great experiment looks like six years in.

In this Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2020 photo, actress Patricia Tackett takes a hit of a marijuana cigarette during WeedCon Wonderland Expo in the Hollywood section of Los Angeles. Public consumption of marijuana is still illegal in Aurora, but could be reconsidered, officials say. AP FILE PHOTO

In this Wednesday, Jan. 22, 2020 photo, actress Patricia Tackett takes a hit of a marijuana cigarette during WeedCon Wonderland Expo in the Hollywood section of Los Angeles. Public consumption of marijuana is still illegal in Aurora, but could be reconsidered, officials say. AP FILE PHOTO

Public Consumption: Moving beyond the great indoors

Keep it indoors, folks. For now.

State law dictates that it is illegal to use marijuana in a public place in any way, including smoking, eating or vaping.

However, Denver has made it possible for certain businesses to apply for licenses to allow for adult marijuana consumption in designated areas, after voting on Initiative 300.

The license is called a Cannabis Consumption Establishment License, and it allows for an existing business to designate an area on the premises of the establishment as an area where it is allowed to get high right there. The license is valid for one year and must be renewed to stay in effect.

The application and license fees are $1,000 each. It’s the high price of getting high away from home.

And with those fees come a roll of red tape to dance around, in the form of supporting documents: A community engagement plan, a copy of the certificate of occupancy, a copy of a valid zone use permit, advisement and acknowledgment form for each owner and manager of the property, a floor plan of the establishment, a health and sanitation plan, a marijuana waste plan, national criminal history records check, a responsible operations plan and employee training manual, an affidavit of lawful presence, an odor control plan, copies of government-issued identification for each owner and manager, evidence of compliance with the Colorado Clean Indoor Air Act, evidence of support from an eligible neighborhood organization, the lease or deed to the building, Secretary of State Certificate in good standing and finally a Secretary of State statement of trade name.

Take a breath.

Upon the application being completed and determined valid to proceed, Excise and Licenses will schedule a public hearing for the application. After the hearing, a final decision will be made allowing continuation of the application process and an inspection will take place.

Once the inspections are completed, a licensing technician will verify that each inspecting agency has submitted the approval electronically, a city license will be issued for the location and operation may begin.

Aurora has nothing resembling the Cannabis Consumption License application, but that doesn’t mean that it isn’t in the cards.

“I think there ought to be some sort of accommodation,” said Aurora Mayor Mike Coffman. “And it is something I am willing to look at. I do feel that we are in competition (with Denver.)”

There are valid reasons for Aurora entertaining the same possibility of allowing something similar to Denver’s Initiative 300 and the Cannabis Consumption License.

“What I want to look at is our retail marijuana stores, hotels and restaurants, in Aurora, to see that they are not disadvantaged because of what Denver is doing,” Coffman said.

Coffman noted that someone who comes to Colorado to visit and books a hotel room in Aurora won’t have anywhere to consume, legally, — since it is illicit to smoke outside and you can’t smoke indoors either. Maybe they would be more inclined to stay in Denver, where the rules would allow for better access to public consumption.

“I understand that this is a competitive industry,” Coffman said. “I don’t want to put one of our 24 (recreation) stores at risk because of what Denver is doing.”

Public consumption, in the sense of blatantly smoking marijuana in public, is seemingly not an issue for the municipal courts. In a city that sees an upwards of 50,000 cases a year, there were 11 cases of public consumption filed last year.

“It’s not something that is usually a primary offense,” said Julie Heckman, Deputy City Attorney for Aurora. In 2018 there were 16 cases in city courts of open display and consumption of marijuana violations.

-—Philip B. Poston, staff writer

Man tired and not looking that awake

Man tired and not looking that awake

Hospitalizations: Enough to make you sick

Sorry, alarmists of Aurora.

While the “hopeless insanity” promised by 1936’s “Reefer Madness” has not quite materialized in Colorado’s emergency rooms in the past six years, there has been a slight uptick in hospitalizations linked to marijuana consumption, officials say.

“Increased availability leads to increased hospitalizations,” said Dr. Andrew Monte, associate professor of emergency medicine and medical toxicology at the University of Colorado Denver-Anschutz Medical Center in Aurora. “It’s a natural phenomenon, but we are not being, like, overrun by cannabis attributable emergency department visits.”

Of the some 300 daily patients who pass through the emergency department at UCHealth University of Colorado Hospital in north Aurora, Monte said one or two of those visits are attributable to cannabis.

Statewide, emergency department visits with marijuana-related billing codes have generally increased since voters passed Amendment 64, according to state data compiled by the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment and the Colorado Hospital Association. Out of some 1.4 million emergency department visits across the state in 2012, slightly fewer than 10,000 of those had marijuana-related billing codes. In 2017, that number had swollen to 21,769 weed-related emergency department visits.

Monte said most patients being admitted for marijuana-related conditions at the north Aurora emergency department exhibit symptoms of a condition known as cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome, which prompts repeated nausea and vomiting among frequent marijuana users. That’s followed by over-intoxication — often the result of mixing marijuana with other drugs — and users who are experiencing psychiatric instability due to marijuana, Monte said.

He added that while the patients of hyperemesis and acute intoxication are often treated and released in a matter of hours, the psychiatric cases can sometimes lead to prolonged treatment for latent mental illnesses.

“Perhaps the most concerning are the psychiatric visits,” Monte said. “That’s the exacerbation of underlying psychiatric conditions and can produce acute anxiety or acute hallucinations. Those are arguably the most dangerous.”

Though infrequent, he pointed to multiple infamous cases of marijuana-involved deaths that were likely precipitated by underlying mental illness, including a Denver man who was convicted of murdering his wife after eating an edible, and a college student who jumped to his death after eating marijuana cookies.

Monte’s conclusions roughly mirror what Aurora first responders have noted related to marijuana use across the city in recent years, according to Shaunna King, clinical services manager for Falck Rocky Mountain Ambulance, the ambulance provider contracted to respond to incidents across the city.

King said ambulance personnel have noticed an anecdotal increase in the number of patients who admit to marijuana use, with many exhibiting symptoms of the vomiting syndrome Monte described, and others who have combined marijuana with other noxious compounds.

“We have seen a small number of patients not just using marijuana recreationally but smoking marijuana cigarettes dipped into or laced with substances, typically formaldehyde, phencyclidine, or both, in crisis requiring medical intervention,” she wrote in an email.

Rates of marijuana-related emergency department visits continue to surpass those related to those prompted by other drugs, but remain below visits prompted by alcohol intoxication, according to state data.

Roughly 4 percent of the 42,410 calls for service Falck responded to last year involved patients who officials suspected of ingesting marijuana, according to King.

And while Monte and King both said cases of inhaling marijuana far exceed cases of people who have consumed edibles, patients who do seek emergency treatment after eating a marijuana-laced product often ingest significant doses.

“The problem with edibles is you can’t guarantee how the dose of the marijuana is spread out within the product; the entire amount could be in one bite of a cookie for example,” King wrote. “ … Continuing to speak from an anecdotal perspective, folks who might not have experienced marijuana in their home states have come to Colorado … They try an edible and don’t feel the effects right away and continue to eat more, eventually requiring medical attention.”

Legislators attempted to curb accidental ingestion of marijuana edibles in October 2017 with a new law that required all products to be stamped with a warning logo, and barred manufacturers from creating products shaped like fruit, humans or animals.

Still, children continue to be admitted to pediatric treatment centers after accidentally consuming edibles, Monte wrote in a paper published in the journal Annals of Internal Medicine last year.

“Such hospitalizations became common when availability of medical marijuana increased, and we still see several each month,” the authors wrote. “These hospitalizations are almost always due to unintentional, unsupervised ingestion of an edible product containing cannabis, such as candy or baked goods.”

Though most cases prove to produce few symptoms in children who inadvertently eat weed, rare cases can become life-threatening.

“There aren’t a tremendous number of those cases, but those should be a sort of ‘never event,’” Monte said. “Kids should never end up ingesting these drugs because it can be dangerous and it really, truly can be life-threatening in children.”

Despite maintaining that those cases are the exception, Monte urged any policymakers considering legalization in other states to understand the increased caseload — albeit small and largely benign — on emergency departments.

“It’s very clear that hospitalizations are increasing, but the volume of them is not huge and generally the conditions that are being treated are relatively easily treated,” he said. “But any state that’s considering legalization should be aware of that and educate their clinicians and their public.”

— Quincy Snowdon, Staff Writer

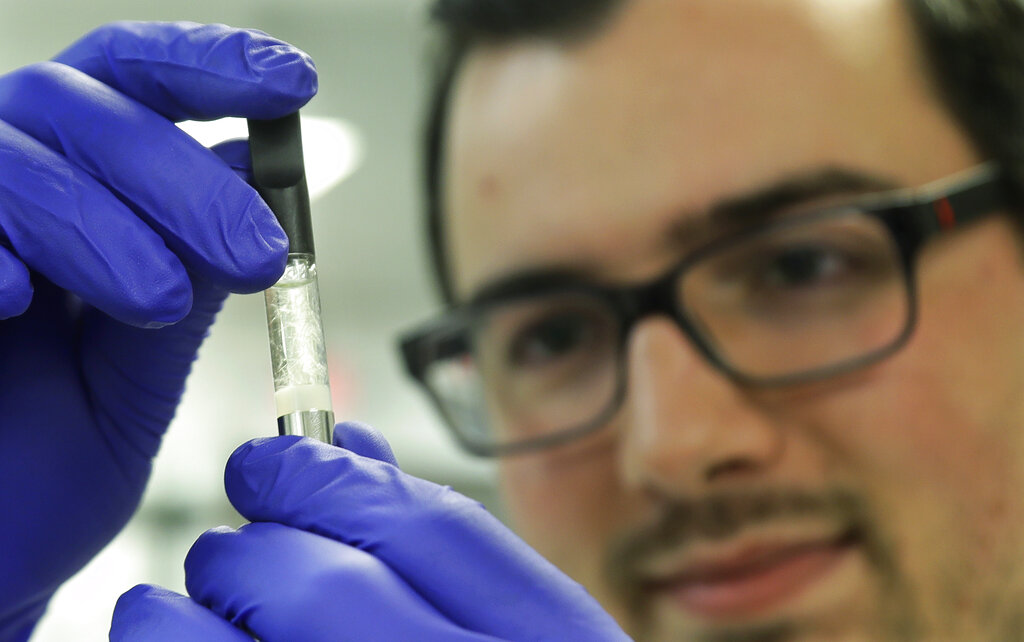

FILE – In this July 19, 2019 file photo, Pierce Prozy examines a Yolo! brand vape oil cartridge marketed as a CBD product at Flora Research Laboratories in Grants Pass, Ore.

FILE – In this July 19, 2019 file photo, Pierce Prozy examines a Yolo! brand vape oil cartridge marketed as a CBD product at Flora Research Laboratories in Grants Pass, Ore.

Public health: Highly investigative

Public health agencies, like Colorado’s state health department, aren’t usually on the hook for funding research. But after the legalization of marijuana in 2014, there were a plethora of questions about how the drug would impact individuals and communities.

There also wasn’t a whole lot of entities willing to take the jump into studying a drug the federal government considered illegal.

For the last several years the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment has been granting research funding to groups that will tackle big questions like whether CBD helps with pediatric epilepsy, if cannabis is useful for treating PTSD and how efficient cannabis is in treating pain compared to Oxycdone, an opioid.

The state health department has infused millions of dollars into research studies. In 2016 the department funded seven different studies.

“We call them impact studies, so these tie directly into the gaps in scientific research,” said Elyse Contreras, the marijuana health epidemiologist at CDPHE. She manages the Marijuana Research Grant Program.

Identifying the gaps was key, she said. There are several of them because the process to approve a cannabis research study is daunting and there just haven’t been enough completed to answer a lot of questions of the substance. That’s why research priorities have ranged from marijuana’s impact on childhood epilepsy to PTSD.

Typically the studies that were granted funds have taken years to complete.

“To do good scientific research in the epidemiology world… clinical trials are the gold standard and can take many, many years to conduct,” Contreras said. “With our limitations from the legislature you have three to five years to spend this money. It’s a limited time for researchers to conduct studies.”

From now on, Colorado State University-Pueblo’s Institute of Cannabis Research will be in charge of how to spend the state’s money for marijuana research. Contreras said while the institute will now seek to answer questions beyond public health with the state-granted money, CDPHE will still have a person on the board of directors to advocate for those types of studies.

“It’s actually a great thing,” Contreras said of the change, because research is typically funded through universities and not public health departments.

While CSU-Pueblo’s new role frees up CDPHE, marijuana research still endures a complicated process because the substance, while legal in 11 states, is a federally illicit drug. Without going through the proper process, agencies and universities risk their own federal funding.

Francis Collins, director of the National Institute of Health, said last month in a C-SPAN interview that it seems a lot of researchers are still deterred by the approval process, even years after it’s been legally approved in multiple states.

“Frankly we know far too little about the benefits and risks of smoked marijuana. There have been very few studies that have actually rigorously tested that,” said Collins, who highlighted that researchers must be approved by multiple federal agencies and use cannabis grown by the federal government that may not reflect the grade of product sold in states like Colorado.

“It’s going to be very hard to interpret data about smoked marijuana when the actual nature of the product is vastly different depending on where you got it,” he said.

Collins is in charge of a marijuana grow at the University of Mississippi where all marijuana for research comes from. Some of the studies CDPHE has approved have used it.

Other researchers, like at the University of Colorado, have side-stepped that complex federal process by conducting observational research.

“Over the years our researchers have learned ways to circumvent these issues,” Contreras said. “For example, some of our researchers have used some of their funding to purchase vans to drive to their participants and have them consume their own marijuana and walk out to the van or to work in a driving simulator.”

Researchers have had to get creative, but Contreras said she believes research has come a long way in a short amount of time.

CSU-Pueblo’s ICR is taking on a plethora of its own research, but the list of priorities has now grown from what CDPHE focused on in previous years. Current research includes exploring perceived risks of CBD, applications of industrial hemp, hemp used in 3D printing and the social support system for people who have quit cannabis.

To put it more simply, “the world is a lot bigger than public health,” Conteras said of the new research that will come out of Colorado funds in the future.

Colorado State University in Fort Collins is in the weeds, too, but research there is limited to hemp.

A research center at CSU dedicated to studying the chemical compounds in hemp is expected to open this spring, school officials said last week.

The announcement comes after the university received a $1.5 million donation from a Golden-based company that makes products out of CBD, a popular cannabis compound with unproven health claims. The money would be used to fund research, cover operating costs and purchase equipment, university officials said.

The facility would allow faculty and undergraduate and graduate students to study the formulation of cannabinoids, separation efficiencies, efficacy testing and more, The Denver Post reported. Cannabinoids can include CBD, also known as cannabidiol.

“Cannabinoids have already been proven effective in a number of clinical applications, and there are more than 100 other compounds that have been identified in hemp that could have an impact in other areas,” said Melissa Reynolds, College of Natural Sciences associate dean for research.

Researchers at the facility would work in partnership with Panacea Life Sciences, a company founded by university alumna Leslie Buttorff that manufactures CBD products for people and pets.

“CSU offers expertise in the complete cannabinoid value chain, including botany, chemistry, biology, psychology, agricultural sciences, statistics and veterinary research,” Buttorff said. “Panacea’s focus in developing scientifically driven and medically focused products will be further advanced with our partnership with CSU.”

The research center will be in the College of Natural Sciences on the Fort Collins campus.

— Kara Mason, staff writer

Wana Brand gummies are removed from their molds to be tossed in granulated sugar, at the Wana Brands facility in Boulder.

Wana Brand gummies are removed from their molds to be tossed in granulated sugar, at the Wana Brands facility in Boulder.

Photo by Philip B. Poston/Sentinel Colorado

EDIBLES: THE HIGH FROM WITHIN

Alas, the lowly, stinky, unpredictable and wholly gross pot brownie is but a distant and often unpleasant memory.

The new edibles are here, and they focus on good taste.

“While still relatively new, the cannabis industry is already in a phase of reinvention,” said Mark Grindeland, Coda Signature Co-founder and CEO. “ Across every aspect of supply and demand, innovative companies are developing new approaches to cultivation, supply chain management, retail, branding and customer experience.”

Coda Signature has made a name creating luxurious chocolates that happen to impart a serious buzz as well.

Company officials say each piece of Coda Signature chocolate starts with ethically sourced cacao. The cacao beans can be traced to specific regions of South America.

“Each of our chocolate varieties brings its own flavor and character — reflecting an individual regions’ climate, traditions and environment. We use whole spices and the freshest ingredients imparting deep and intense flavors that blend perfectly with our cannabis oil,” according to online marketing material.

These are not your father’s attempts at finding a way to eat dope.

“We are able to produce premium products thanks to longstanding relationships we’ve cultivated with community farmers in South America,” said Marji Chimes, Chief Marketing Officer at Coda Signature. “Knowing where our premium ingredients such as cocoa and cane sugar are sourced helps ensure Coda Signature maintains the level of quality we aspire to across all product offerings.”

The attention to culinary detail is no buzz killer.

To make sure that the THC is evenly distributed throughout their chocolate bars, Coda Signature uses a homogenization process to mix the chocolate and the cannabis, after which, they send each batch of chocolate bars and truffles to a testing lab to ensure that each square has the proper dosage.

Micro-dosing is a different method of ingestion that traditionally is saved for taking hallucinogens, such as LSD — but no longer. Micro-dosing can test tolerance or raise tolerance, in the case of THC, to reap the medical benefits without an overwhelming feeling of the psychoactive compounds in marijuana.

There are several companies that offer micro-dose edibles. These manufactures claim that a microdosed THC experience offers a more relaxed disposition, increased stress tolerance and an overall feeling of happiness, more regularly. Moreover, micro-dosing assists in pain relief, mental health and lessened anxiety, manufacturers claim.

And since the user is micro-dosing, there is no overwhelming concern for eating too many milligrams of THC when enjoying the edibles.

Gummies are the top choice of cannabis eaters, according to Headset, which is a data analytics service provider for the cannabis industry.

“We collect receipt-level data from participating retail cannabis stores through a direct integration to their point-of-sale system. We also use government reported data to inform our algorithms and improve the quality of our data set,” their website reads.

Wana Brands gummies are spun and coated in sugar, at their Boulder, CO facility. Wana Brands is the leading distributor of marijuana edibles in dollars sold in the United States.

Wana Brands gummies are spun and coated in sugar, at their Boulder, CO facility. Wana Brands is the leading distributor of marijuana edibles in dollars sold in the United States.

Photo by Philip B. Poston/Sentinel Colorado

The top gummy producer is Wana Brands and their name is household in the industry. Wana holds the number one or number two position for all states in which it has operated for more than a year, in dollars sold, according to BDS Analytics. And in Colorado, Wana owns six of the top 10 SKUs in the state and produces almost half of the gummies sold. The company holds the number one or two position for all states in which it operates.

In order to assure consistency, and quality, regulating the dosage that goes into each individual gummy, Wana will test the dosage twice. After their in-house testing, they send the product off to a third party to do one final test. By state regulation, all products must be sent to a third-party independent lab for verification.

“We have multiple checkpoints for dosing,” said Nancy Whiteman, CEO for Wana Brands. “We require that all the oil purchased (from cultivators) comes with results for potency, pesticides and contaminants from a third party lab.”

Consistency is key. But so is consumer safety. Wana claims the title of industry leader in development of education of budtenders, as well as consumers. They have developed a program for bud tenders that features extensive online and in-person training.

Wana suggests that consumers should always start low and go slow. For a novice consumer, they recommend a 2.5 mg to 5 mg dose. They also suggest that the consumer wait 60-90 minutes before eating more edibles to account for the delayed effects. These training sessions also cover how their products work in the body, information on the endocannabinoid system, micro-dosing and CBD.

A machine at the Wana Brands facility cuts the gummies into molds to solidify into shape and display the required THC logo on each gummy.

A machine at the Wana Brands facility cuts the gummies into molds to solidify into shape and display the required THC logo on each gummy.

Photo by Philip B. Poston/Sentinel Colorado

Endocannabinoids are naturally-produced substances that mimic cannabinoids. Scientist discovered the substances in the 1990s and believe they help maintain homeostasis in the body.

“This knowledge can empower sales associates to provide consumers with accurate and appropriate recommendations, ensuring consumers have the best possible experience when they leave the store,” Whiteman said.

That evidence is anecdotal as the industry works to catch up research with claims.

Denver Public Health states that Colorado’s definition of one edible dose is 10mg. Most edibles are offered in higher amounts than the 10mg recommendation, but there are ways to split up the total dose in the products.

Coda Signature chocolate bars have segments on them, similar to most consumer chocolate bars, making it easy to separate a 100 mg bar into 5mg pieces — ensuring what they say is a responsible and safe experience.

“We always recommend starting ‘low and slow’ with any infused edible product, which means starting with a lower amount of THC until you know your own comfort level, and waiting up to two hours for the effects,” Chimes said. “Everyone is different when it comes to cannabis consumption, and the industry standard of 10mg THC per serving may affect some people more intensely than others. Additionally, our chocolate bars and Fruit Note gummies contain 5mg THC per serving, which makes it easier for consumers to start with a lower dosage.”

— Philip B. Poston, staff writer

Ali Maffey, retail marijuana education manager for the Colorado Department of Health and Environment, talks to reporters after a news conference that announced the rollout of the $5.7-million, state-sponsored advertising campaign Monday, Jan. 5, 2015, to educate marijuana consumers in Denver. The “Good to Know” advertisements focused on marijuana laws and health effects, including the ban on use in public places, age restrictions, DUI laws, the dangers of overuse and other concerns related to the use of the products. The campaign has since ended. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

Ali Maffey, retail marijuana education manager for the Colorado Department of Health and Environment, talks to reporters after a news conference that announced the rollout of the $5.7-million, state-sponsored advertising campaign Monday, Jan. 5, 2015, to educate marijuana consumers in Denver. The “Good to Know” advertisements focused on marijuana laws and health effects, including the ban on use in public places, age restrictions, DUI laws, the dangers of overuse and other concerns related to the use of the products. The campaign has since ended. (AP Photo/David Zalubowski)

DUI ENFORCEMENT: How stoned you are

According to staff at the Colorado Department of Transportation, you can never really know how stoned you are.

When lawmakers decided on the legal limit for driving and partaking in marijuana, they threw the age-old question — “Are you good to drive?” — into some jeopardy.

Countless Coloradans hop into the car after imbibing the sticky green stuff, whether by blunt or tincture brew, and never encounter a cop. They drive to work, the grocery store and probably to the dispensary. That’s nothing new.

“People have been driving high since the stagecoach, most likely,” said Sam Cole, a spokesperson for CDOT’s Statewide Safety Program.

Mostly, there are no accidents. Everything is groovy.

The thing is, a Colorado cop might not agree — even if you think you’re not stoned, and a blood test comes back below the legal limit for THC. THC stands for tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive component of pot that gets you high.

That limit is five nanograms per milliliter of your blood.

Politicians, pot advocates and bureaucrats alike have long argued that the five nanogram limit is arbitrary and not rooted in scientific research. But thousands of folks have been convicted of a DUI and put on the hook for thousands of dollars, even if they felt they weren’t impaired, with the help of that threshold.

In 2017 there were about 26,500 case filings with at least one DUI charge, according to CDOT. That’s for all drugs, including marijuana and alcohol. But alcohol-related case filings outnumbered those cannabis impairment cases, with 13,277 compared to 4,792.

In Aurora, police said they conducted 1,138 DUI and Driving Under the Influence of Drugs arrests in 2018. That number dropped to 953 arrests in 2019. High blood alcohol toxicology reports outnumbered those for cannabis six to one.

Drunk driving is still a bigger issue than driving high, Cole said. Many more accidents are caused because of drinking than THC.

When Colorado cops handed DUI charges over to prosecutors with toxicology results, conviction rates were similar for folks driving above both booze and weed’s legal limits — near 90 percent. That’s according to the 2018 CDOT report.

But were they really too impaired to drive?

Alcohol blood alcohol content tests are considered established science. But with pot, that limit is still up for debate.

A bong-rip or THC gummy can affect two people very differently, barely affecting a seasoned stoner while catapulting the average Midwestern greenhorn into outer space. THC can be stored for different amounts of time in different bodies, depending on fat content, diet and exercise regimens. The cannabinol can appear latent in blood even if a person hasn’t smoked for days or more.

With this in mind, Glenn Davis said the five nanogram limit should be reconsidered. Davis was a cop for over two decades in Littleton and regularly conducted traffic stops ending in DUI tests. Now, he’s the Highway Safety Manager at CDOT.

“To me, the number is irrelevant,” he said of the five nanogram limit.

State lawmakers settled on that number preparing for marijuana legalization in 2014.

Davis said the most important factor in a DUI case is the opinion of the officer pulling you over. He explained that cops have varying degrees of expertise tracking whether you’re too impaired to drive. Some are experts. Cops can also call in experts to the scene of a traffic stop, day or night, to help conduct roadside tests.

Your performance on those tests is the kicker — not a possible blood test down at the police station office, Davis said. You have to consent to that test, and penalities are stiff for declining. Your license can be confiscated for a period of time, and you could still be charged with a DUI.

Or perhaps you’ve been sipping on liquor and took a hit off a joint before putting pedal to the metal? A cop could recommend DUI charges against you if they think the two drugs, combined, made you too impaired to drive in spite of low toxicology reports.

Along with a re-think of the stoned driving limit, Davis also hopes lawmakers will allow cops to use cursory roadside THC tests instead of hauling folks down to the station for a blood test.

But for now, the five nanogram limit and drug-sensing process stands. That’s food for thought before you eat that edible and drive.

— Grant Stringer, staff writer

FILE – This Jan. 9, 2018 file photo shows Sen. Cory Gardner, R-Colo. The legal marijuana industry often finds the doors locked at banks, its money unwanted because the drug remains illegal under federal law. Gardner and others are trying to find a way to allow cannabis businesses access to banks. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

FILE – This Jan. 9, 2018 file photo shows Sen. Cory Gardner, R-Colo. The legal marijuana industry often finds the doors locked at banks, its money unwanted because the drug remains illegal under federal law. Gardner and others are trying to find a way to allow cannabis businesses access to banks. (AP Photo/J. Scott Applewhite, File)

Financing: Weed it and reap

Far from being a budding industry, cannabis is now a fleshed-out and publicly-traded industry worth billions, saturated with volatile stocks and plenty of sometimes complicated and sometimes ludicrous business ideas. (See Sriracha-flavored tinctures.)

The devil’s lettuce has tormented stockholders, business owners and Colorado Congressmen trying to forge a more stable financial future.

Weed is a multi-billion dollar industry, despite being federally illegal. And stockholders are trying their hands to get a piece of the pie. Unfortunately for them, the marijuana industry is still not as stable as investors would like. Marijuana stocks overall “substantially underperformed” the S&P 500’s total return of 27 percent in the last year, according to Investopedia, bringing back a cool negative 46 percent return. The investment encyclopedia described an industry on shaky ground.

“Most of them have paltry sales figures and almost none of them are profitable,” the site said of publicly-traded marijuana companies.

It’s a reality detached from the buzz surrounding the cannabis industry.

“Maybe another misconception about the industry is that we wake up in the morning and cash rains down,” said Peter Marcus. The former journalist is now a spokesperson for Terrapin Care Station, a cannabis company with six dispensaries on the Front Range including two in Aurora. “Most companies are running on a shoestring budget,” he said.

Locally, investors are still banking on marijuana making it big.

Last spring, City officials celebrated the opening of Aurora’s first marijuana grow house. Millions of dollars of capital poured into the top-of-the-line, 1,800- plant facility owned by Bud Fox.

But in the facility, at least two massive safes guarded countless pounds of buds, buttressed by steel mesh embedded between the drywall.

Marijuana may be a bona fide business, but security is still a concern for many growers and dispensaries.

That’s because banks, under federal law, are still unable to accept money from dispensaries. Doing so could attract the attention of prosecutors from the U.S. Department of Justice and the squinting eye of U.S. treasury department analysts on the hunt for money laundering.

Some dispensaries turned to beefed up security and massive safes like Bud Fox’s, Morgan Fox said. Based in Washington D.C., Fox is a spokesperson for the National Cannabis Industry Association, an advocacy and lobbying group.

“It’s a huge issue,” Fox said of security. He pointed to a recent uptick in robberies and burglaries of dispensaries racking Denver. Last year, Denver businesses reported 5 robberies and 122 burglaries. That’s a three-year high, according to the Denver Post.

A fatal shooting of a security guard during an armed robbery at an Aurora pot shop in 2016 is a stark reminder of how critical security is.

Aurora police referred The Sentinel’s inquiry for similar data in Aurora to a record request. That request had not been processed by press deadline.

Fox said most people don’t know many Colorado dispensaries are already putting their funds in banks because of the security risk.

He said banks are naturally risk- adverse. To compensate for the risk of a possible crack-down because of connections with the marijuana industry, banks have simply spiked the price of doing business. Checking accounts, money transfers and the like can cost much more than usual, putting a stress on a nascent industry.

Plus, Fox said the banks that are working with marijuana businesses in Colorado are not accepting new clients. There can be year-long wait-lists, he said.

Marcus knows the struggle well. He would not disclose the name of the bank that Terrapin is working with, but he said the costs are very high.

“They’re able to do that because it is difficult to find banks that can take your money,” he said.

It’s a problem now in the sights of Colorado Congressmen.

Both Democratic Rep. Ed Perlmutter and Republican Sen. Cory Gardner sponsored bills last year to bring marijuana banking out of the shadows.

But the proposals are still just that. Marcus said the bills face challenges in the Republican-controlled Senate, and it’s not likely either will see the light of day.

That reality has left Colorado officials to shore up a more stable path forward for banking pot revenues.

Gov. Jared Polis announced an initiative Feb. 3 to provide resources and clear up the network of regulations for banks interested in taking on cannabis clients. The ultimate goal, Polis said in a press release, is to get 20 percent of the state’s banks working with marijuana companies by the end of June.

— Grant Stringer, staff writer

PROSECUTING POT: The green-headed monster grows

In Colorado, the days of having your adult life upended after being caught smoking a pungent doobie are largely over.

If you’re in your car or under the age of 21, it’s a different story. But following the implementation of the state’s historic Amendment 64 on Jan. 1, 2014, the casual consumption of small amounts of marijuana in the Centennial State has become blase at best.

Still, the intersection of marijuana and Colorado law enforcement remains a complex thicket of unintended consequences, officials say.

Large-scale marijuana grows spun out of the black market and anchored in metroplex suburbs have become the primary concern for federal, state and local authorities. Last May, the U.S. Attorney for Colorado announced officials arrested 42 people on federal charges stemming from massive, illegal marijuana grows along the Interstate 25 corridor. Among those indicted were two Aurora residents eventually convicted of curing some 10 pounds of weed and growing nearly 900 marijuana plants — enough for about 150,000 joints — in their home at 20050 E. Doane Dr.

State law allows residents to grow 12 marijuana plants inside any given home, barring special circumstances.

“Colorado has become the epicenter of black market marijuana in the United States,” local U.S. Attorney Dunn said in a statement following the announcement of dozens of marijuana-related arrests in May. “ … But this investigation may just be the tip of the iceberg.”

Arapahoe County District Attorney George Brauchler talks with reporters during a DEA raid into numerous homes in southeast Aurora where illegal marijuana grows were suspected. PHOTO BY QUINCY SNOWDON/The Sentinel

Arapahoe County District Attorney George Brauchler talks with reporters during a DEA raid into numerous homes in southeast Aurora where illegal marijuana grows were suspected. PHOTO BY QUINCY SNOWDON/The Sentinel

Indeed, the Aurora couple implicated in last spring’s investigation are among dozens of city residents Aurora police have encoutered when sussing out suspected residential home grows in recent months.

“We have just been nonstop,” Aurora Police Sgt. William Revelle said of the law enforcement response to illegal marijuana production in the city. “We can’t keep up.”

Revelle, who has been assigned to the department’s narcotics unit for the past seven months, said his team serves two or three search warrants on suspcted marijuana grows across the city every week. If he had more resources, Revelle said officers could easily serve 15 such warrants per week.

“It would not surprise me if every single neighborhood in Aurora had a grow somewhere in it,” he said.

The proliferation of black market grows in the city significantly accelerated following legalization, Revelle said. When assigned to a now-defunct drug enforcement unit in the mid-1990s and late-2000s, he said he never encountered an illegal grow operation.

“I never came across a grow until after it was legalized,” Revelle said.

Indeed, organized crime case filings, which is often what prosecutors pursue in black market grow cases, have seen a “significant increase since 2014,” according to the state department of public safety, jumping from 31 such filings in 2012 to 112 in 2017.

George Brauchler, district attorney for the 18th judicial district, said his office is currently involved in multiple cases tied to illegal marijuana grows — all with more than 20 named defendants.

“I still think that the black market is more prolific, more professional and more robust than I’ve ever seen it in 25 years of being in the criminal justice system,” he said. “I’ve just never seen anything quite like it.”

Marijuana plants line a driveway outside a home in southeast Aurora after a massive DEA raid on homes across the city in Oct. 10, 2018 PHOTO BY QUINCY SNOWDON

Marijuana plants line a driveway outside a home in southeast Aurora after a massive DEA raid on homes across the city in Oct. 10, 2018 PHOTO BY QUINCY SNOWDON

Those cases prove much more difficult to prosecute, according to Brauchler. The case that Dunn announced last spring was the culmination of three years of work.

“The black market thing has become much more of a resource suck,” Brauchler said.

He added that all of the investigatory wire taps he’s signed off on since he took office seven years ago have been related to drug cases. Half of those have been related to marijuana operations.

What’s more, Brauchler said his office has filed 15 first-degree murder cases related to “illegal marijuana transactions” in recent years.

“The ones that are just inexplicable to me are the first-degree murders and all the other violent crime related to the illegal transaction of marijuana,” he said. “I can rationalize it in terms of, well, it allows them to export it with I guess a greater feeling of impunity, they avoid the taxes and the regulation. I get all that stuff. But come on. People getting killed over marijuana? In a market where you can go buy marijuana? That is just a head-scratcher.”

Violent crime crept up in the six years after voters signed off on Amendment 64, with the number of statewide murders, non-consensual sex offenses, aggravated assaults and robberies ticking up about 25 percent. In Aurora, there were about 63 percent more violent crime cases filed two years ago when compared to the 2012 statistics.

Revelle said more marijuana production in the city could be a contirbuting factor to the bump in local crime as warrants served on illegal grows often lead to the seizure of additional drugs and firearms. This week, a warrant served on a large grow operation in 7,000-square-foot home the city’s Saddle Rock neighborhood led to the collection of 13 guns — including seven assault rifles — five kilograms of cocaine and several pounds of psychedelic mushrooms, Revelle said.

“I definitely think violence is up, to an extent, because of marijuana,” he said.

Statewide, drug violations generally increased between 2012 and 2018, though Aurora tallied a decrease in such offenses over the same time period, according to Colorado Bureau of Investigation statistics. But the types of drugs being seized on local streets have completely flipped since voters signed off on retail marijuana regulation in 2012, when nearly two-thirds of the drugs Colorado authorities were nabbing comprised weed or hash. In 2018, the latest data available, the proportion of weed grabbed across the state was down to just 22 percent of all drugs seized. Methamphetamine now makes up the highest share at about 42 percent.

That shift resulted in about half the number of marijuana-related arrests across the state in 2017 when compared to 2012, according to data compiled by the state’s Division of Criminal Justice. Overall court filings related to marijuana also plummeted across the state, dropping from about 11,220 in 2012 to 7,402 three years ago, which is the latest data available. About half of the 2017 cases stem from charges of possession of marijuana by someone under the age of 21, which became law in 2013.

Aurora’s 18th Judicial District roughly mirrors those trends.

But Brauchler said there have been enough drug offenses in his jurisdiction in recent years to warrant hiring a prosecutor who only handles marijuana cases. And Senior Chief Deputy District Attorney Darcy Kofol has been busy since she took over the new role, Brauchler said. She’s currently in the midst of a three-week trial stemming from a large-scale marijuana operation based out of California.

Both Brauchler and Revelle said marijuana legalization in nearby states could stem black market growth in Colorado, though Colorado’s nieghbors — particularly those to the east — don’t appear poised to sign off on legal reffer any time soon.

“As more states legalize it, it will slow demand,” Revelle said. “But until then, we’re going to see this trend continue, I think, for two or three more years, and we’ll continue to see the violence.”

—Quincy Snowdon, staff writer

FILE – In this April 25, 2013 file photo, attorney Michael Evans, left, listens in his office in Denver as his client Brandon Coats talks about the Colorado Court of Appeals ruling that upheld Coats being fired from his job after testing positive for the use of medical marijuana. Photo/Ed Andrieski, File)

FILE – In this April 25, 2013 file photo, attorney Michael Evans, left, listens in his office in Denver as his client Brandon Coats talks about the Colorado Court of Appeals ruling that upheld Coats being fired from his job after testing positive for the use of medical marijuana. Photo/Ed Andrieski, File)

WORKPLACE: Taking legal weed out of the work shadows

The difference in federal and state law has made cannabis use somewhat murky on a bevy of fronts, like in the banking industry or how it’s studied by scientific researchers.

This year in the Colorado legislature, Democratic Aurora House Rep. Jovan Melton is attempting to make that separation a little clearer, at least for workers who want to partake outside of their 9-to-5 jobs.

Melton introduced HB20-1089 last month. It would prohibit employers from firing a worker for an off-duty activity that is legal under state law, even if it’s illegal at the federal level. Marijuana currently falls into that category.

The bill doesn’t have any Senate sponsors yet. Melton says he’s “shopping” the legislation around, but could easily see a Republican signing on because it embodies a libertarian spirit, “that the federal government can’t tell us what to do,” he said.

Even less than halfway through the session, the bill has seen an uphill battle.

The biggest push back so far is coming from labor groups and the business community, Melton said.

“I would say, some of them, especially the (groups) that deal with heavy equipment or federal contracts are just worried that this may violate some of their no-tolerance policy agreements,” Melton said.

Tony Gagliardi has been at the helm of the Colorado chapter of the National Federation of Independent Business, which advocates for independent and small businesses, for about 15 years. NFIB and other business organizations, like the Denver Metro Chamber of Commerce, are against 1089. They say it violates a business’s right to a drug-free workplace. This is despite the more recent addition of marijuana-related businesses that are joining business organizations.

“The issue goes back to when Colorado first passed medical marijuana and it wasn’t too long after that I got a call from one of our field service people and they had called on one of the new dispensaries and asked if we could sign them up as members,” Gagliardi said.

The organization, which is made up of about 7,000 small Colorado businesses that mostly have fewer than seven employees, agreed that marijuana businesses would face similar issues to other businesses.

“They’re going to have issues like anybody else,” he said. “They’re going to have worker comp issues. As it relates to that they can join NFIB.”

But when it comes to legislation like Melton’s bill, Gagliardi and NFIB won’t support that interest. The organization has been consistent on the issue. In 2015, NFIB submitted an amicus brief to the Colorado Supreme Court case Coats v. Dish Network, which ruled that an employer could terminate an employee for engaging in an activity that isn’t lawful under state and federal law.

In that case, Brandon Coats, a quadriplegic who held a medical marijuana card in Colorado, was fired from his job at Dish Network after testing positive for marijuana. Coats and his lawyers said the termination was discriminatory. But the Colorado Supreme Court, in a split vote, said otherwise: “Under the plain language of… Colorado’s ‘lawful activities statute,” the term ‘lawful’ refers only to those activities that are lawful under both state and federal law.”

Gaglardi said he sent the brief NFIB wrote to Melton because it’s relevant in their opposition and that the legislation could open up employers and workers to “unbearable risk.”

“I thought there’d be some push back from the business community. I wasn’t expecting as much, but I think we can get there because Amendment 64’s intent was to regulate marijuana like alcohol,” Melton said. “So we’re saying it’s OK to drink when you’re off work. Why is it not okay to consume marijuana?”

Melton said he sees the concern from the business community, but doesn’t see the legislation as an extreme change to business practices.

“We’re not saying someone should go to work high,” he said. “We’re just saying if someone went to a concert on Saturday night and did an edible and then went to work on Monday and they’re sober, they shouldn’t be penalized for doing something that’s legal.”

— Kara Mason, staff writer

See, BD, a primer for every person, animal and situation

It’s all about being receptive, and that you can’t have too much of a good thing.

CB1 receptors are a key element of the endocannabinoid system. These receptors are activated by THC, providing the euphoric feeling from ingestion. Unlike THC, CBD doesn’t fit into CB1 receptors, in turn preventing CBD from causing the consumer to get high. This is because CBD doesn’t react with CB1 in our bodies. In fact, CBD can sometimes reduce the feeling of euphoria from THC when both are ingested simultaneously.

CBD is an abbreviation for cannabidiol, and is the second most prevalent active ingredient in cannabis, after THC. It can be derived directly from the hemp plant, which is a cousin to the marijuana plant, and doesn’t contain a substantial amount of the psychoactive, THC. 0.3% THC to be exact.

The list of benefits of CBD is not short, but the most prevalent uses are to address anxiety relief, pain relief, and to a grander purpose, it can be used as a treatment for seizures and cancer.

The strongest evidence for CBD effectiveness is in treating childhood epilepsy syndromes, such as Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome, which traditionally doesn’t respond to anti-seizure medications. According to a report by Harvard Healthcares Publishing, in numerous studies CBD was able to reduce the number of seizures that take place and in some cases stop the seizures altogether.

CBD can also be used to treat chronic pain. A European Journal of Pain study showed that applying CBD to the skin, through a salve or balm, could help lower pain and inflammation resulting from arthritis. A separate study showed that CBD inhibits inflammatory and neuropathic pain, which are two of the most difficult chronic pains to treat.

There are a slew of companies that produce a bevy of CBD products, but the FDA has approved only one CBD product, Epidiolex, which is a prescription drug product used to treat two rare but severe forms of epilepsy, LGS and Dravet syndrome.

Dog treats are displayed at the Cannabis World Congress & Business Exposition trade show, Thursday, May 30, 2019 in New York. The treats contain non-psychoactive cannabidiol, CBD. They are marketed by DabbinDoge of New Providence, N.J. (AP Photo/Jeremy Rehm)

Dog treats are displayed at the Cannabis World Congress & Business Exposition trade show, Thursday, May 30, 2019 in New York. The treats contain non-psychoactive cannabidiol, CBD. They are marketed by DabbinDoge of New Providence, N.J. (AP Photo/Jeremy Rehm)

While there is evidence that CBD does work for some symptoms, it isn’t a cure all, like some companies who sell the product claim. And these days, CBD isn’t necessarily used solely for ailments.

A mascara by Milk Makeup called Kush is a CBD product available for purchase. The product description on Amazon reads, “NATURALLY LIT Conditioning CBD-rich cannabis oil fuses heart-shaped fibers to lashes for thickness without the fallout. The hydrating formula also fills the hollow fibers for a double dose of volume,” whatever that means. Some reviewers have called the product “flaky.” That’s an apropos description for using a chemical compound ideally intended to treat pain, not fill out eyelashes.

It doesn’t stop with make-up. There are a litany of borderline absurd products with the three letters attached. For example, there are CBD suppositories and lube for the more intimate moments, CBD toothpaste, CBD toothpicks, CBD infused athletic wear, CBD infused bed sheets, CBD hair pomade, CBD facemasks, CBD sugars, CBD bitters for libations and what is possibly the most popular, CBD treatments for pets.

The University of Colorado is currently in the midst of a clinical trial in which the school is researching the effects of THC and CBD on pain management.

The National Center for Health and Statistics reports that approximately 76 million Americans suffer from chronic pain. The number of those affected is higher than that of cancer, diabetes and heart disease, combined. Dr. Cinnamon Bidwell believes that number might be as high as it is due to the ubiquity of the chronic pain and how to manage it.

The study began June 1, 2018 and is estimated to run through Oct. 31, 2021, with the completion of the study estimated to be March 31, 2022.

The global hypothesis of this study is that the observations of the self-report and objective measures of the effects of marijuana edible projects by pain patients who choose to use these products will vary as a function of the ratio of THC to CBD in their blood. It also hypothesizes that that cognitive impacts observed will differ by the THC/CBD ratio in blood. Saying that the higher rate of THC, the more the cognitive effects will be demonstrated.

CBD trends don’t stop at human consumption. It is also said that CBD oil can be used to treat ailing pets. And the ailments it is used to treat are that in the same vein of human use.

There has been no formal study on how CBD affects pets, it is known that it reacts to endocannabinoids in the same manner it does humans. According to the American Kennel Club, there is anecdotal evidence from canine owners that it helps with seizures and control pain.

The AKC Canine Health Foundation sponsored a study through the CSU College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical sciences which evaluated the use of CBD on treatment-resistant epileptic dogs, during 2016-2017. Conducted by Dr. Stephanie McGrath, the study found that of the 16 dogs used in the study, 89 percent saw a reduction in the frequency of seizures.

In this Sept. 25, 2018 photo, bottles of maple syrup and olive oil infused with CBD marijuana extract are displayed for sale at the Village Bloomery medical cannabis dispensary in Vancouver, British Columbia. On Oct. 17, 2018, Canada will become the second and largest country with a legal national marijuana marketplace. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

In this Sept. 25, 2018 photo, bottles of maple syrup and olive oil infused with CBD marijuana extract are displayed for sale at the Village Bloomery medical cannabis dispensary in Vancouver, British Columbia. On Oct. 17, 2018, Canada will become the second and largest country with a legal national marijuana marketplace. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Furthermore, the study showed that the higher concentration of CBD in the blood, the lesser the frequency. “We saw a correlation between how high the levels of CBD oil were in these dogs with how great the seizure reduction was,” McGrath said.

The AKC has a few good tips when purchasing CBD for your furry friends. Try to buy organic, don’t price shop — put simply, the higher the price the better the quality — it’s best to buy liquid CBD, making it easier to adjust dosage, in lieu of a treat with a set dose already distributed, and always get the analysis of what you are buying.

— Philip Poston, Staff Writer